Cleopatra Wash

Fiction

Photos and short story by Matthew O’Brien

The desert, so distinct in the mid-afternoon, was a blur at sundown. The dirt roads and dry falls and furrows were one. Three hours ago an inviting bright beige, the terrain had been dyed a dark copper color. The sky was bruised.

Breathing heavily, his red-and-blue pinstriped T-shirt splotched with sweat, Michael Walsh stood at an unmarked trailhead and surveyed his surroundings. His eyes were bloodshot. Sand powdered his face. His car was somewhere out there, within a half-mile of the trailhead, but he wasn’t sure where. He took a swig from his almost empty water bottle and hurried into half-light.

A few hundred feet from the trailhead, Mike found one of his markers — metamorphic rocks that formed an arrow aimed at his car. He exhaled and followed the arrow, soon arriving at the intersection of three dirt roads. He searched for a second marker — an arrow he’d drawn on a road with the heel of his hiking boot — but couldn’t find it. Was he at a different intersection, he wondered? Had the wind erased the arrow? Or, as a sense of dread set in, was he simply not seeing it?

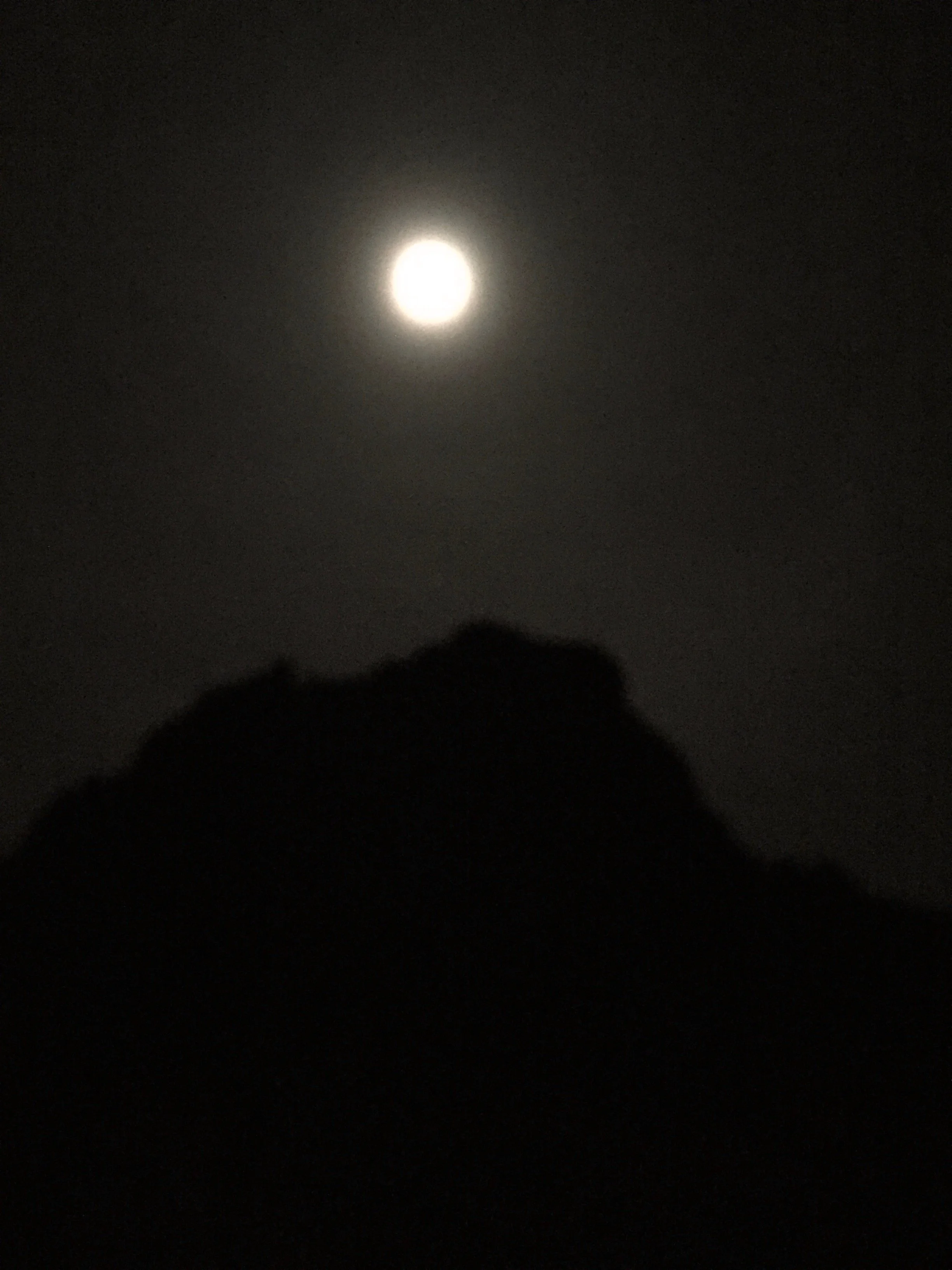

He walked the middle dirt road, which faded in and out of the desert floor, for more than a half-mile, but didn’t arrive at his car. Slipping out of his backpack, he removed his keys from the bottom pouch and pressed the unlock button. All he heard was the distant hoot of an owl; the only light he saw was the amber, egg-shaped moon, which had risen as quickly as the sun had set.

Feeling adrift and in need of an anchor, he backtracked to the rock arrow. Once again, it led him to the intersection of the dirt roads. He started up the road to his right, which promptly swerved and skirted a shadowy ravine. He picked up a rock and overhanded it into the void. Five seconds later, it clattered against the floor and he backed away from the ledge.

He was confident his car wasn’t on this road — he would’ve remembered the deep ravine — but he was getting desperate. He removed the keys from his cargo shorts and again hit unlock. Could someone have stolen his car? He quickly dismissed the notion, as the area was deserted, and dug into his pocket for his phone. No service.

The sky was a velvety black and the moon had risen well above the jagged mountaintops. The stars popped. Michael had a stark realization: He could search all night and not find his car. Having perused maps online that afternoon before leaving his apartment, he knew the trail he’d hiked ran north to south and the main road was north of the trailhead. He decided, while he still had the energy and his bearings, and it was not too late at night, to walk the three or so miles to the main road and seek assistance there.

It was winter—the ideal season to hike this trail during the day — and the temperature had dropped twenty degrees since he climbed out of his car. The sweat on his neck and back began to chill. He wasn’t worried about hypothermia, as the temperature rarely dipped below fifty, but he wanted to be as comfortable as possible on the march to the main road. As he took off his floppy hat and stuffed it into the backpack, and dried his hair and neck with a beach towel, he thought about his wife. What if they were still together and she’d accompanied him on the hike? Would they have been able to find the car? If not, how would she have reacted? With understanding? Frustration? Anger? Would the situation be better or worse?

His thoughts shifted to his young son. He’s why I’m walking back to the main road, he declared, strapping on a headlamp and aiming it at the ground. If not for him, I’d throw my keys, phone, and backpack into the ravine and lie down on the sand. Let nature have its way with me.

He dabbed his stomach and lower back with the towel, then slipped into a cotton hoodie. After downing the final swig from the water bottle, he started across the desert.

* * *

Mike’s fifteen-year, rollercoaster relationship with Las Vegas had reached a new low. In the past nine months, he’d been laid off, his wife and son had moved into her parents’s house, he had trouble finding work, and he didn’t have anyone to confide in. (An abyss, which he couldn’t explain, had formed between him and most of his friends and family members.)

Instead of visiting a therapist, he’d made it a point to hike more often — to escape the green-felt jungle and sit, legs crossed, on a red rock. It gave him balance and perspective. It quieted his mind, which was as loud as any Strip casino. Las Vegas likes to kick a man when he’s down, and Mike had found many of the locals to be self-centered and unreliable, but the wilderness surrounding the city had never disappointed him. It was more forgiving than the metropolis and seemed to impart more answers than questions.

He had endured the boulder-strewn Gold Strike trail and soaked in its hot springs, as bighorn sheep danced atop the cliffs. He’d explored abandoned mines, then looped around the Liberty Bell Arch, and was rewarded for enduring the early fall heat: a view of the Colorado River from one thousand feet above. Vermilion rocks, bursts of green, and sweeping views characterized Kraft Mountain Loop. Judging by what he read online that Sunday afternoon, Cleopatra Wash was as promising as any of these trails. One article included it in its “Top 10 Vegas-Area Hikes,” and reviews raved about its flora and fauna, geology, solitude, and vistas of Lake Mead. He wrote down directions to the trailhead and stuffed them into the back pocket of his shorts. He then scooped up his backpack and exited his apartment, hiking boots hanging from his shoulder.

He took Lake Mead Boulevard crosstown and stayed on it as it snaked between Frenchman and Sunrise mountains and dead-ended at Northshore Road. He turned left, driving along the perimeter of the lake for twenty miles. Just before mile marker thirty, he hung a right on an unmarked dirt road. According to the directions, the trailhead was two and a half miles down the road, which was rocky and overgrown. His Kia Sportage moaned and contorted, its undercarriage occasionally scraping the surface, and he wondered if he’d taken a wrong turn. As the road got rougher, he decided to park and walk.

A drive that he thought would take an hour took more than an hour and a half — and he’d still not reached the trailhead.

Climbing out of the car, he was greeted by a breeze that was warmer and gentler than in northwest Las Vegas. He popped the trunk and slipped out of his Vans and into his boots. He then rifled through the backpack, removing the floppy hat and pulling it over his head. Since it was winter and later in the afternoon, and he wanted to lighten his load, he also removed an extra bottle of water and tossed it into the trunk. Finally, he locked the car and continued down the road on foot.

As the road began to fade, he drew the arrow on it with the heel of his boot. He detoured around a dry fall and collected and arranged the rocks that were aimed at his car. Just down from the rock arrow, he found the trailhead — the mouth of a dry wash that funneled between two low ridges. He glanced over his shoulder, surprised that no one else was around.

Both intimidated and inspired by the solitude — after all, he was hiking more often to get away from everyone and everything — he started down the wash, boots crunching in the gravel. The wash snaked, a surprise around every bend: a dry fall, yellow wildflowers, an oddly shaped boulder. The straightaways were as wide as a football field and flanked by steep, black cliffs capped with a metallic-blue sky. In the narrows, he touched the smooth walls with his outstretched hands.

Yet he couldn’t deny that something was amiss. Why, on an idyllic Sunday afternoon, did he have the trail to himself? Why did he keep crashing into cobwebs? Why were the ropes rigged to the dry falls and boulders torn and tattered?

He discovered the answer to his questions at the end of the trail: Five to ten years ago, when Lake Mead was full, the wash emptied directly into it; but since the lake had receded — a bathtub ring revealing its high-water mark — a twenty-foot drop and a quarter-mile now stood between Mike and the shore. Even if the drop had a rope, Mike doubted he would’ve descended it, as the dry lake bed was marshy and mosquito-infested. Cleopatra Wash may have been a top-ten, Vegas-area hike several years ago, he thought, but it wasn’t one now. Its payoff had literally evaporated.

Wanting a wider view of the lake than this nook afforded, Mike climbed out of the wash and over a low, brittle saddle. As he eased down the slope, the red rocks shifted beneath his boots like broken glass. He lost his balance and cut his shin. It’s all right, he told himself. It’s not officially a hike unless you bleed a little bit.

As the slope leveled off, Mike looked up. The lake — a palette of pastels — was spread before him. He’d hoped to swim — he wore his bathing suit under his shorts and packed the towel — to cool off and cleanse himself of the past year. To wash it off of him. But the lake was uninviting and the daylight was beginning to fade.

He pulled the towel from the backpack, wet a corner of it with water from his bottle, and dabbed the cut on his shin. He then spread the towel over the rocks and sat down. The reflection of a rolling, sandstone mountain shimmied on the surface of the lake, and a pair of gulls, camouflaged by cirrus clouds, squawked somewhere overhead. Mike tried to take in the view, to be present in the moment, but his thoughts turned to his wife and son. When his wife told him the bank was repossessing the condo she owned and they’d lived in for three years and, instead of moving into an apartment together, as they’d planned, she thought they should live apart, he fought the idea, more for his son than anyone else. But his wife was adamant. She also said he could see his son whenever he wanted to. Assuming he and his wife would reconcile, as they had many times before, he rented a two-bedroom apartment a half-mile from her parents’s home, in hopes that she and the kid would soon join him.

A month and a half later, his hopes were fading. His wife hadn’t shown any interest in getting back together and had ignored or rejected his attempts to reconnect. Something had changed, but he wasn’t sure what. Had she given up on him, he wondered, staring blankly at the lake? Did she meet someone else? Was it a combination of the two?

Mike blinked and refocused on the lake, now a reddish-brown. In one motion he stood, scooped up the towel, and stuffed it into the backpack. He then scrambled over the saddle and angled down into the wash, quickly turning toward the trailhead.

* * *

As he marched toward the main road, the beam of Mike’s headlamp — the same shape and color as the moon directly above it — illuminated sand, creosote, and the occasional prickly pear cactus. The sand was compact, the shrubbery sparse. Other than the patter of his boots it was silent. The temperature had continued to drop, but, because he’d been walking for fifteen minutes, he wasn’t cold. If not for the circumstances and his fear of stepping on a rattlesnake, this would’ve been a pleasant moonlight hike.

He looked up, in search of headlights in the distance. The moon surrounded him with a halo of light — he didn’t have to use the headlamp — but, beyond that sphere, darkness reigned. Of course, he consoled himself, that doesn’t mean the road is not out there somewhere; maybe there aren’t any cars on it. He was confident he was walking in the right general direction, away from the trailhead and to the north, but he wondered if he was off by twenty or thirty degrees. If he, for example, was trending northeast instead of due north. Through personal experience, he’d learned that could add miles to a hike or even cause you to become lost.

The terrain rose, then pitched to Mike’s left. As it leveled off and rolled toward a wide mountain pass, he thought he smelled smoke. He paused and sniffed the air, confirming his suspicion, and continued forward. The scent grew stronger.

Entering the pass, he glanced to his right. At the foot of a towering sandstone mountain, flames licked the darkness. A campfire? Again, he looked for the road, and then started toward the flames.

Using rocks as steps, he scaled a forty-five-degree incline. When he reached a plateau at the base of the mountain, he placed his hands on his knees and looked up. His brain was slow to process what he saw: a spacious, horizontal hollow; a soot-stained oil drum; a man with a lined, sunken face standing over the barrel, staring into the flames. Mike straightened up, glanced over his shoulder. He then turned to the man.

“Excuse me,” he said.

The man didn’t flinch or look up, and Mike wondered if he’d heard him. He took a few tentative steps forward. As he raised his hand, in preparation to repeat what he’d said, the man took a swig from a can of beer and again dropped his head.

“I’ve been expecting you,” he said to the flames.

Mike paused. He assumed the man had mistaken him for someone else or was drunk or crazy.

“Sorry to bother you,” he said. “I got turned around. Can you point me in the right direction?”

The man emerged from behind the barrel. He was not much taller than the drum, barefoot, and dressed in a black T-shirt and cutoff shorts. A hunting knife hung from his hip, and he was bald or his head was shaved.

“You ain’t bothering me,” he said in a slow, raspy voice. “What do you need?”

“I’m trying to find the main road.”

Still clutching the can, the man scratched his head and shuffled closer.

“The one that leads into town,” continued Mike. “I think it’s that way”— he pointed in the direction he’d been walking — “but I want to be sure.”

“You can get there that way,” slurred the man, “but that ain’t the way I’d go.”

“Is the road far from here?”

“Depends on how you look at it.”

“About a mile or so?”

The man nodded. “Something like that.”

“Thanks,” said Mike, giving up on him and starting down the slope.

“Don’t go running off,” said the man.

Mike paused on one of the steps and turned around and watched as the man disappeared into the shadows of the hollow. He stood upright, hands at his side, prepared to defend himself if the man charged him with the knife. He dared him to try something. He wanted him to.

The man emerged from the shadows gripping an extra can of beer. Before Mike could decline it, the man underhanded the can to him. Mike caught it clumsily.

“It ain’t cold, but it’s wet,” said the man, flashing a gummy smile.

In the beam of his headlamp, Mike scanned the can’s familiar blue-ribbon label and the lid. He couldn’t recall the last time he had a drink, but it must’ve been before the separation. Since his wife and kid had moved out, he’d avoided alcohol, fearing that it would make him depressed or irrational. He’d wanted his head to be as clear as possible.

But, he was finally forced to admit, that approach had failed. He was miserable and his head was cluttered with counterproductive thoughts. One beer couldn’t make things any worse. Furthermore, his lips and throat were parched.

Mike scaled the steps, casually wiping the lid with the bottom hem of his hoodie. Reaching the plateau, he popped the top. The man thrust his can into the air, spilling beer onto Mike’s boots, and proposed a toast.

“To taking the right path!” he said.

“I’ll drink to that,” said Mike, tapping his can against the man’s and sipping from it and licking his lips. “Where do you get beer around here?” he asked the man.

“The campground.”

“They have a store there?”

“Some campers gave ’em to me as they were packing up.”

Mike took another pull from the can. “Is that what you’re doing here? Camping?”

The man stroked the gray stubble on his chin. “Guess you could call it that.”

Mike peered into the hollow, his headlamp and the fire betraying its dark recesses. A pair of coolers was pushed against the far wall, and an assortment of fishing rods stood at attention in a nook. To the right of the rods, a mountain bike leaned clumsily on its kickstand. A tattered camping chair straddled the front border of the chamber, providing a full perspective of the pass, mountains, and sky.

“It’s not a bad view,” said Mike, surveying the stars and already a little lightheaded.

“You gotta pay a fortune for a view like this in Vegas,” said the man. “I get it for free. There’s no power bill, either.”

“No one bothers you? Park rangers or the cops?”

The man shook his head. “You’re the first person I’ve seen ’round here in months.”

The man reached into the pocket of his shorts, producing a mini-flashlight. He clicked it on and, starting slowly toward the fire, swept the beam over the floor, which was flat and sandy. Mike followed a few steps behind.

The sweat on his neck and lower back beginning to chill, Mike stepped over a bag of charcoal and pulled up at the near side of the drum, feeling the soft heat on his stomach, chest, and face. He cut off his headlamp. Using a long, crooked stick, the man stoked the flames. Embers disappeared into the night like shooting stars.

“I was hiking Cleopatra Wash,” explained Mike, pointing vaguely in the direction from which he’d come, “and I lost track of time. When I got back to the trailhead, the sun was down and I couldn’t find my car.” He laughed at himself. “I decided to walk to the main road—figured I could get help there or find the dirt road I came in on and follow it to my car—and that’s when I saw the fire.”

The man stared cross-eyed into the warped, rusted barrel.

“Do you know that trail?” Mike asked over the flames.

The fire crackled. The man downed another mouthful of beer. “I know all the trails,” he finally said, still focused on the flames. “Could walk ’em blindfolded.”

“I got the feeling I was the first person to hike it in a while.”

“I walked it not too long ago.”

“I guess it was popular five or ten years ago, when the lake was full. But then it dried up and people stopped going there.”

Following another prolonged paused, the man asked Mike, “What brought you here?”

Mike sipped his beer and then glanced at the man, whose face was distorted by the rising heat. He thought about explaining that he’d been trying to hike at least once a week, and he found that trail online and it had good reviews, so he figured he’d give it a try, but he simply said, “I’ve had a lot on my mind.”

Finally, the man looked up.

Mike turned away, then again found the man’s blurred visage. “It’s been a rough year.”

The man glanced over his shoulder, toward a full-size mattress topped with a balled-up bedsheet and accompanied by a milk crate that served as a nightstand.

Realizing the man had likely had a few rough years of his own, Mike nodded. “I got laid off, my wife left me, I’ve been struggling to find work. It’s been one thing after the other. Everyone and everything is telling me to leave Las Vegas, but it’s not that simple. My son is there, and I can’t start over at my age.”

“How old are you?”

“I’m thirty-seven.”

“That ain’t nothing. You’re always younger than you think you are.”

Mike forced a smile. After swallowing a swig of beer, he said, “Out of the blue, my wife started bringing up things that were bothering her: an ex-girlfriend I kept in touch with, my temper, my lack of motivation as a freelancer. We’d talked about these things before, and I wasn’t sure why she was bringing them up again. Then she said she thought we should live apart.

“We’ve broken up before, but this time feels different. Something has changed; I just don’t know what.”

“All that matters is it has changed,” said the man.

Mike closed his eyes, nodded. “I guess you’re right. I just want to give it one more try. For my son more than anyone else.”

“She ain’t coming back,” said the man firmly.

Shoulders slumped and face blank, Mike looked at the man. The man met his gaze. Mike waited for him to smile or speak, but he did neither. He didn’t even blink.

Mike was stunned that someone he’d just met would say such a thing. What did he know, thought Mike? He’s a drunk who lives alone in a cave.

Mike stared at the ceiling, which was ten feet high and black with soot, and exhaled. He looked down at a plastic pail overflowing with cups, plates, utensils, and charred pots and pans, and stroked his square, cleanly shaved chin. Finally, he finished his beer. After placing the empty can in the pouch of his backpack, he glanced at the man and said, “Thanks for the drink.” He then turned, switched on his headlamp, and started across the chamber.

* * *

When Mike reached the front border of the camp, the man called out to him.

“Hang on a second,” he said.

Mike watched as the man staggered over to the coolers, popped the top of the one on the left, and removed a bottle of water. He met Mike at the border and handed him the bottle.

“One for the road,” said the man, patting Mike roughly on the shoulder.

In the beam of his headlamp, Mike inspected the bottle. The label was crisp and bright, the water clear. “Thanks,” he said, stuffing the bottle into a side pocket of his backpack. He unzipped the bottom pouch and dug out his wallet. “Let me give you some money for the beer and water.”

The man shook his head. “Keep the money. Sounds like you need it more than I do.”

Before Mike could protest, the man began along the border, pausing at its periphery. A narrow, shallow trail hugged the mountain, then jerked and descended in the direction of the pass.

“This’ll take you where you’re trying to go,” said the man. He traced the trail with the beam of his flashlight.

“The road is that way?” asked Mike, pointing toward an elevated stretch of trail that was visible in the moonlight.

“That’s the way I’d get there.”

Mike thanked the man again, then extended his hand toward him. The man shook it, his grip strong and calloused, and looked him in the eye. After shouldering the backpack, Mike started down the trail and, approaching a bend, glanced back to make sure he was not being followed.

He paused in the middle of the pass, pulled the bottle of water from the side pocket, and twisted the cap, breaking the seal. Relieved that the bottle had not been opened — maybe it was given to the man by the same campers who gave him the beer or maybe he stole it from a store or cooler — he took a sip of the water. It wasn’t cold, but it was fresh and clean. He downed a swig, then licked his lips.

After returning the bottle to the backpack, Mike continued across the pass to the trail the man had recommended. It skirted the opposite mountain, dipped and swelled, and trended to his left. It seemed to be taking him back toward the lake. He walked the trail for another quarter-mile, then scrambled up a boulder and surveyed his surroundings. There was still no sign of the road.

He decided to walk the trail for another quarter-mile. With each tentative step, he became less confident he was headed in the right direction. The man had tricked him, he thought, perhaps intentionally. Nothing he said could be trusted; the entire conversation was a waste of time. If he had not detoured to the fire and had continued on his way, he’d be at the main road and perhaps en route to his car. He pictured the man standing over the barrel, a fresh beer in hand, laughing, and he considered backtracking to the camp and confronting him about everything he’d said.

Mike continued down the trail. It rose again, then jerked to the right and straightened. As he looked up, the trailer lights of an eighteen-wheeler appeared from behind a bald knoll and crawled westward across the desert. He could hear its dull roar.

Matthew O’Brien is a writer, editor, and teacher who lived in Las Vegas for twenty years and is currently based in San Salvador, El Salvador. His latest book, Dark Days, Bright Nights: Surviving the Las Vegas Storm Drains (Central Recovery Press 2020), shares the harrowing tales of people who lived in Vegas’ underground flood channels and made it out and turned around their lives. You can learn more about Matt and his work at www.beneaththeneon.com.