Driving is Hell in Sin City

How About a Little Trauma to Spice Up Your Daily Commute?

By Shainna Alipon

My front dash-cam captured the moment it all happened: my sheer panic, my increasingly hysterical fuck’s as I realized I got into a car accident, and my shrill and hyperventilating voice as I told my boyfriend that I had gotten into a wreck. The one thing my dash-cam didn’t capture was the moment I got rear-ended. I had no rear camera to bear witness.

Moments before the crash, I was driving home and chatting with my boyfriend. We were only three months into our relationship and the honeymoon butterflies were at its peak. I ended my day at UNLV earlier than I usually did so I could rush home and hop on a video call with him. I was understandably excited for our most special form of date, with him being in Belgium and me here in Vegas.

“I am almost home-ish,” I say to my boyfriend as I gently slow down at my highway exit.

I didn’t even finish coming to a stop when my car lurched forward as someone bumped into me from behind. I crashed into two other cars in front of me and then I drifted into the next lane where I dented the car over there, too.

I remember feeling helpless and deeply wronged. I was already doomed to be in a long-distance relationship, and now I couldn’t even spend time with my boyfriend because I had to deal with this car accident? The feeling of loss of control continued when my mother decided for me that I should get a lawyer. The very next day I was dragged to a law office. Looking back, getting a lawyer involved right away was the best course of action. But I didn’t want that back then. I just wanted everything to go away, to go back to normal.

Of course, it never did. Anxiety would wash over me every time I would drive a car. Paranoid, I would constantly watch my rear-view mirror more than I would actually look in front of me while driving. Once, a viciously tailgating truck sent me into a panic attack and I switched into the next lane without looking. Luckily, the car next to me was able to swerve into the bike lane. It took two years of panic-induced driving incidents like this before I finally realized I needed help.

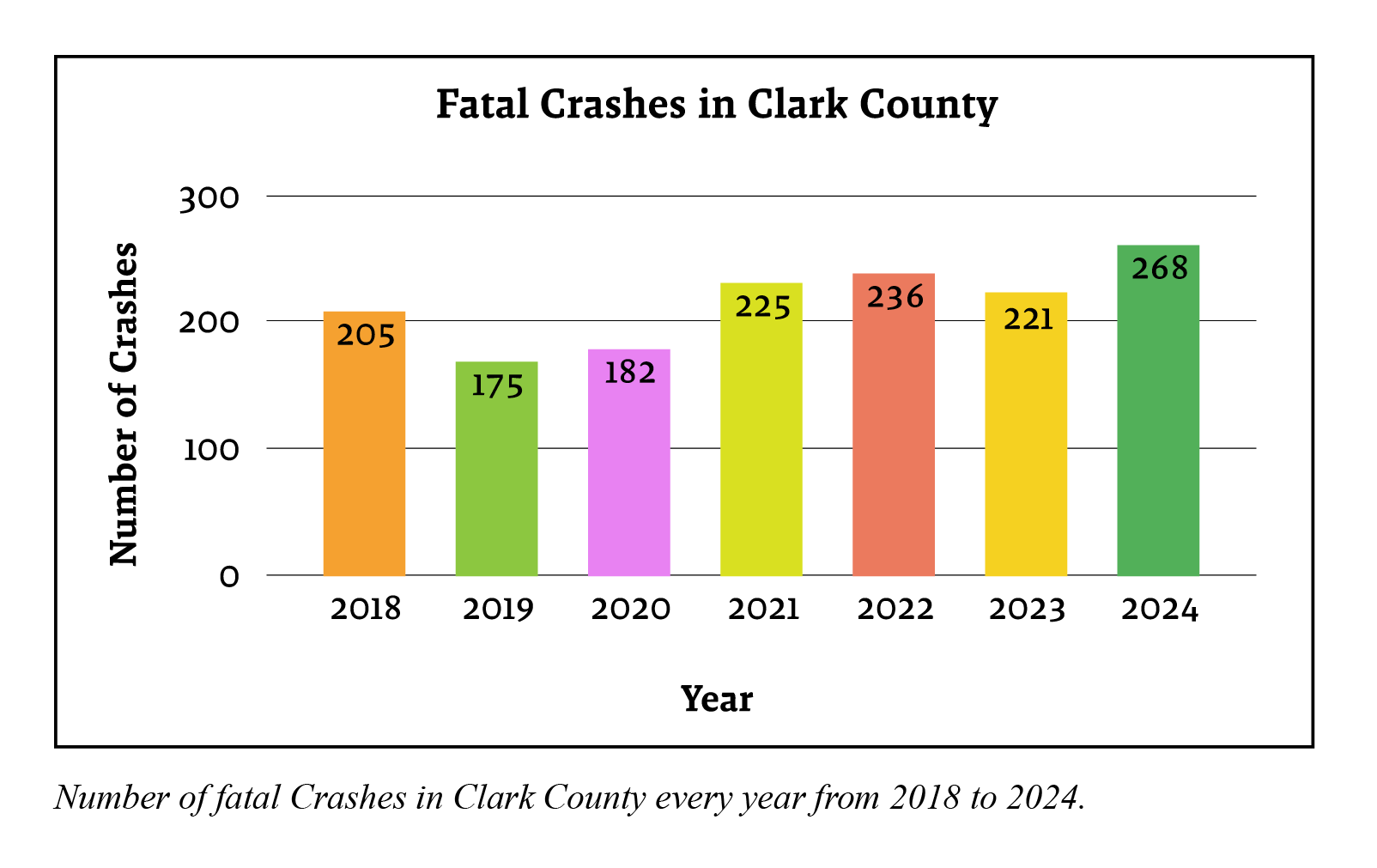

Driving in Las Vegas can ruin lives. Car accidents don’t just traumatize people—they kill them. Zero Fatalities, a program from the Nevada Department of Transportation and the Nevada Department of Public Safety, counted 293 dead drivers and passengers from car crashes in Clark County in 2024. There were 268 fatal crashes at the end of 2024, an increase from 2023’s total of 221 and an even greater increase from 2018’s 205 crashes.

“[Traffic] safety is all about difference. Differential in speed, differential in behavior,” says Pushkin Kachroo, a professor and transportation researcher at UNLV’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Danger arises when cars suddenly need to slow down and the cars behind them are still going at a higher speed. This sudden change creates the highest risk for accidents. Everyone driving at a similar speed, whether fast or slow, makes the roads safer.

That makes sense. I was almost at a stop at the highway exit when I was rear-ended, and the car behind me was still going highway speeds. I don’t think they saw just how many cars were stopped at that ramp exit.

Pushkin also says that driving temperaments can be different for the same person depending on their circumstances and the time of day. He gives the example of someone driving to work in the morning with a meeting first thing in the day compared to someone going home at the end of the workday. They may be more rushed in the morning and more relaxed on their way home.

It was around 4 p.m. on a Friday when it happened. When the woman who hit me got out of her car, she looked dazed and confused. She must have had a long day at work. Maybe it was a long week at work that caused her attention to slip.

“If you make roads very comfortable, it can have a dangerous effect on safety, because then you feel comfortable and you start driving faster,” Pushkin says. He defined comfortable roads as ones that are wide and have smooth visibility, which describes most roads here in Vegas. With a smirk, he added that potholes actually force people to drive slower.

Erin Breen, director of UNLV’s Road Equity Alliance Project, agrees. Erin has been a traffic safety advocate in the state for nearly 30 years. She speaks to many audiences about traffic and pedestrian safety and helps lobby driving laws and transportation projects.

“Pedestrian safety is a three way street,” Erin says. “It’s the driver and the pedestrian, but it’s also how the road is built. It actually has way more to do with it than the driver or pedestrian. Larger lanes will enable you to go faster and feel comfortable.”

She says that roads will self-police—narrower lanes will force drivers to slow down.

An example of roads self-policing can be seen with mini roundabouts. A handful were installed along Cimarron Road between Sahara Avenue and Oakey Boulevard as the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported in late January.

Residents were complaining about speeding in the area. The posted speed limit is 25 mph, but traffic data showed drivers going 40 mph. Jace Radke, public information officer for the city, says over a phone call that this road was chosen for this project because houses directly face the road, and there is only one lane in each direction plus a center turn lane. The roundabouts brought speeds down from 40 to 26 mph.

“We [as drivers] break the law all the time,” Erin says. “And this whole culture of ‘I won’t get caught’ is why our fatalities for pedestrians are so high right now.”

And indeed, many people really don’t get caught. Erin claimed that there is currently a police shortage in the city. If an officer stops someone for going 10 miles over the speed limit, then someone going 40 over will speed past them, so the officer has to weigh out who is more dangerous.

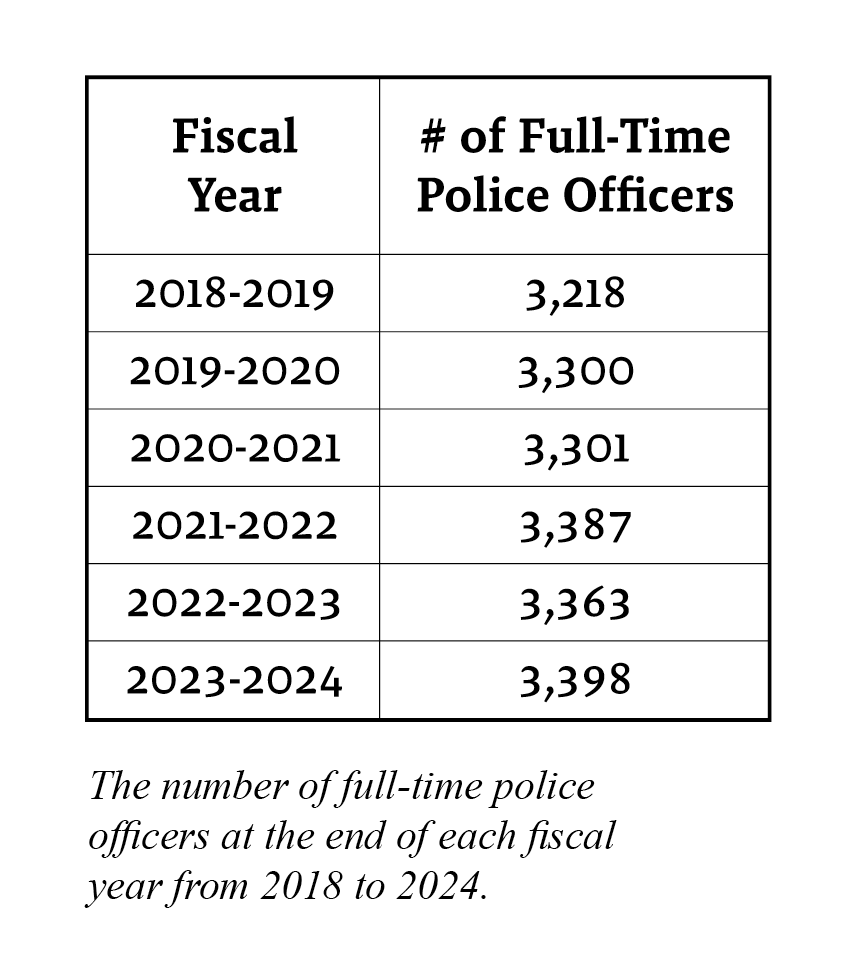

News articles from 2023 and 2024 mentioned a police shortage in the city, though a recent news clip from Fox 5 Las Vegas in November 2024 reported that there is a newfound interest in joining the police force after years of declining recruitment numbers. This is the only local news station that has reported anything recently on police numbers. The LVMPD’s annual reports seem to corroborate an increase of officers, with the force reporting 3,387 full-time police officers at the end of the 2021-2022 fiscal year, to 3,363 in the 2022-2023 fiscal year, and back up to 3,398 officers at the end of the 2023-2024 fiscal year.

LVMPD denied requests for an interview. Instead, I spoke with Greg Munson, a retired police captain who worked at LVMPD for over 26 years. His tenure included nine years as a motor cop, a traffic officer on a motorcycle.

“Traffic has not increased their numbers,” Greg says confidently. “I can speak to that even today because I talk to those guys every once in a while. When you’re a motor [officer], you’re always a motor, as they say.”

Greg claims that the key to better traffic law enforcement is to have over 160 motor officers, like when he was in the force in 2009 and fatalities in the valley were lower. (According to the 2012 LVMPD annual report, there were 84 fatal collisions in 2009. The lowest recorded year for fatal collisions in the Las Vegas valley was in 2011, when 70 fatalities occurred).

Erin claims that the best education for following driving laws is by getting a ticket and that it will change your behavior for six months. Greg disagrees. He described the thought process of someone who just got stopped for a ticket.

“So now you slow down, but only in that area where you got stopped,” he says. “But it only lasts for a few hours, and then the person goes back to their bad habits.”

He did stress that tickets work for the majority of people—and referenced his previous claim of having more motor officers—but it highly depends on the area, economic status of a person, and ultimately their personality.

“Criminals don’t care. They’re going to do what they do, right,” Greg says. “We have people in prison for felony DUI because they’ve been arrested more than once. Three, four, five times.”

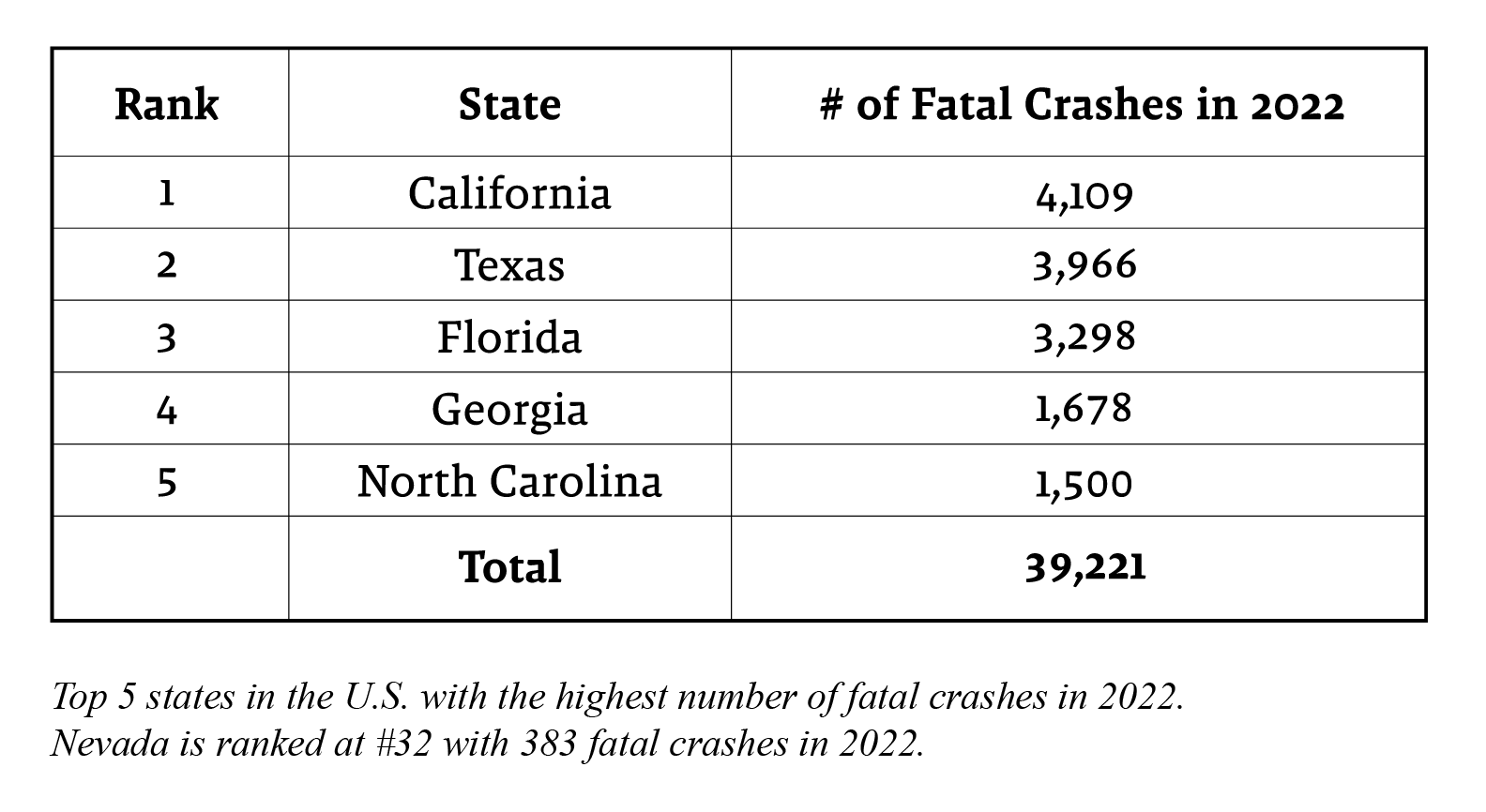

How Nevada compares to the whole country’s traffic fatalities can be difficult to grasp. Below are the top five states with the most fatal crashes in 2022 and where Nevada ranks, according to the Fatality and Injury Reporting System Tool (FIRST) by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Note that Nevada is 32nd place with 383 crashes—it doesn’t seem to be bad at all compared to California’s whopping 4,109.

However, there are many factors that affect driving fatality rates per state. These include population, how many miles people drive on average, rural versus urban areas, state traffic laws, types of vehicles driven, and weather in the state.

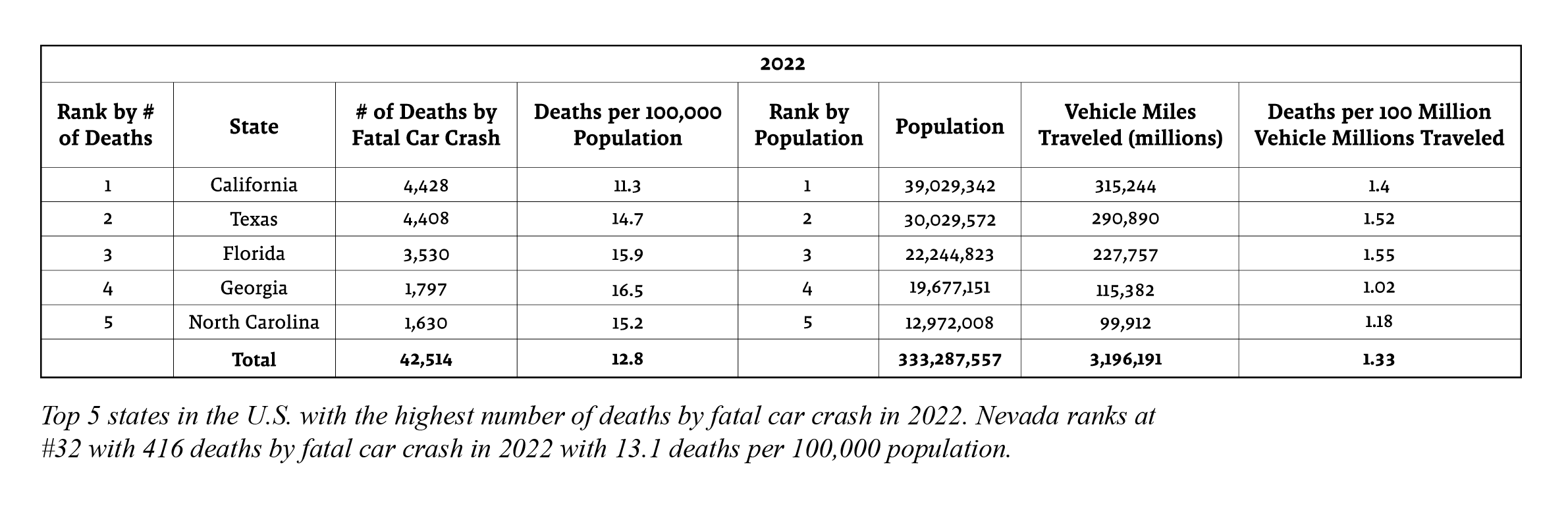

These numbers can be put into perspective when considering a state’s population and total miles driven, as the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety put together using data from FIRST. California lost 4,428 lives to fatal crashes in 2022. Nevada had 416. However, looking at the list of states that had the most to the least amount of deaths by fatal car crash is similar to the list of states ranked by most to least populous. It makes sense that the states with the most people in it happen to have the most fatal crashes as well.

To understand the data, we also take into consideration how many miles on average a state’s population drives. For example, Nevada and Arkansas have similar populations, but there is a higher amount of vehicle miles traveled in Arkansas versus Nevada. Arkansas then has a higher rate of deaths per miles traveled—1.67 deaths per 100 miles traveled vs Nevada’s 1.5. Arkansas is more rural than Nevada, which may account for the fact that vehicles travel more there despite having a slightly lower population than Nevada. Each state has unique challenges that make traffic safety a personalized effort.

Andrew Bennett, the director and one-man team of the Clark County Department of Office Safety, says that one of the state’s challenges is that a vast majority of people did not learn how to drive here, so their driving norms are adopted from somewhere else. There are even more unique challenges on a county and city level, like how Clark County holds two-thirds of the state’s population and how the county has both urban and rural centers while other counties only have rural areas. Andrew also attributed Las Vegas’ 24-hour nature as the reason we don’t have one designated rush hour because people work all kinds of shifts.

“I think we're feet away from chaos at any given point,” Andrew says rather seriously.

Luckily, Andrew believes that there is a smooth relationship between the different departments and governments regarding roads and traffic safety. Implying its necessity, he gave an example of Charleston Boulevard—depending on which part of the road you’re on, it can be a city, county, or state road. Jurisdiction lines can get blurry, but they all work together on corresponding construction projects and pass complaints to the correct individuals when one is received in the wrong jurisdiction.

“We all work together so people don't have to think, ‘Who do I reach out to?’” he says.

He encouraged me and others to learn how and when to reach out to government officials for traffic safety feedback in our communities—not just elected officials, but to staff as well. Andrew says that just that morning, before our interview, he received feedback from a crossing guard. He explains that he trusts her and what she says because she’s the one out there every day, twice a day.

Andrew’s traffic safety views align with Vision Zero, an initiative in the valley across many departments and jurisdictions with the goal to eliminate all traffic fatalities. He emphasized that “redundancy is key” and that road infrastructure must be designed with the assumption that people will always make mistakes and, occasionally, poor choices. With this in mind, roads can be designed so that people slow down and that crashes are reduced or even eliminated.

Greg likes the idea of Vision Zero and other initiatives that push for zero fatalities, but believes that ultimately it’s not achievable because to achieve that, one would need to start at the root cause. “To truly make an impact, one has to start with the drivers, our people,” he says.

Erin says that something she knows to be absolutely true about people and transportation is that they never see themselves as the problem or the victim. This statement rings true in “story time” videos of driving horror stories across social media. It always involves the other driver doing something wrong, but it’s never about admitting their own mistakes while driving.

“No one ever, ever leaves home thinking they’re not coming home or that they're going to take somebody else's life. It's never in their thought process,” Erin says somberly. “Yet, all of us do stuff every day that could cost us our life or take someone else’s.”

Greg was quick to answer when I asked him what his bad driving habit is. He admitted that when he’s mad or has something going on at home, he talks on the phone and won’t be paying as much attention as he’d like to while driving. He doesn’t even believe in using Bluetooth as a communication method while behind the wheel, adding that it’s “hands-free but not mind-free,”.

Andrew says that his bad driving habit might be that he’s anxious when he drives. He believes that when you’re traveling—driving, biking, walking—you should be able to enjoy it. But he doesn’t.

I didn’t even have to ask Erin about her own driving habits. After recounting a story of a fatal car crash that was recently dismissed in court, she asked rhetorically, “Am I a perfect driver?” She shook her head. “Do I know more than most? Yeah, but do I go 10 miles over the speed limit? Yes.”

Many times over the course of our conversation, Erin emphasizes the human element in traffic safety. We do dumb things and make mistakes. “My job is to make you more aware of what those dumb things are,” she says. She corrected herself. “The human things.”

Unfortunately, the dumb human things can be costly. Andrew got into traffic safety 16 years ago when his sister was on her way home from UNLV and a drunk driver going the wrong way crashed into her on Interstate 215. Lindsay died of her injuries two days after the crash. A young Andrew is seen crying in this article by the Las Vegas Sun. The image shook me as I had just interviewed a determined now adult-Andrew a few hours earlier.

I understand. I didn’t know before, but I went through these interviews for this article hoping for answers to magically cure my driving anxiety, to make my PTSD from my car accident go away. Of course that didn’t happen. No amount of interviews and zealous writing about traffic safety and driving culture can restore my feeling of safety on the roads.

“The last 16 years has been an incredible journey of answering that question of ‘why,’” Andrew says. “Why did this happen? Why did it happen to my sister? What can be done to prevent them [car accidents]?”

Though my tragedy is not like Andrew’s, those questions have echoed in my mind throughout the process of this piece and in the years following my accident.

It’s no easier for the officers who have to report to the scenes of fatal accidents.

“Every time a family member comes running up to you and crying like, ‘Is he alive?’ And you don’t want to tell them that [they’re not],” Greg says. “It’s hard to deal with that stuff as a cop because you see it every day.”

But at the same time, Greg says it can be frustrating too because a fatal collision is preventable, whether on the victim’s part or the other driver’s.

Erin explains how it can be so easy to drive unsafely: “It all comes down to not having a plan.”

She advises people to plan for construction and to give yourself enough time to get to your destination. Use maps to check your route twice—once and then again right before you leave in case travel times have changed.

“You [need to] take personal responsibility for your actions. You’re always sober. You give yourself enough time to get to where you’re going and you wear your damn seatbelts,” Erin declares.

Greg emphasizes paying complete attention to the road, even if it’s drivers that aren’t directly affecting you: “Could you tell me three things that people did before they cut you off? Or cut somebody else off?”

Ultimately, Andrew doubles down on the idea of personal responsibility while driving: “There's so many different ways to get home safely at the end of the night that don't involve drinking and driving or being impaired and driving, so we need to make sure that, as a culture, we promote that responsibility.”

What I did gain from these interviews was acceptance and patience—a deeper understanding of how I drive and of how others drive. I hope you did too.

Shainna Alipon (she/they) is a freelance multimedia journalist who enjoys writing about culture and science. This proud bisexual Filipino-American wants you to know that you are loved and her cats give you kisses!